“Do not be alarmed when you hear of the great riots. Your trio are safe, and we trust the worst is over.”

Lavina Goodell, July 17, 1863

At a time when many cities have seen protests, with some erupting into violence and clashes with police, the chaotic scenes displayed in our modern media might look somewhat familiar to Lavinia Goodell, since in the summer of 1863 she and her parents experienced New York City’s deadly draft riots firsthand.

By early 1863, as the Civil War dragged on, Union forces faced a serious manpower shortage, so President Lincoln’s government passed a strict new conscription law making all male citizens between the ages of 20 and 35 and all unmarried men between 35 and 45 subject to military service. All eligible men were entered into a lottery. Men could buy their way out of service by either hiring a substitute or paying $300 to the government, but since that was a year’s salary it was an option available only to the wealthy. Because African Americans were not considered citizens, they were exempt from the draft. Anti-war newspapers published inflammatory attacks on the new draft law, aimed at inciting the white working class.

While riots also occurred in other cities, none was hit as hard as New York. The first lottery of the new draft was held on Saturday, July 11. After a day of relative calm, protests began on the morning of Monday, July 13. Lavina, who was with her her father in the office of his anti-slavery newspaper, the Principia, in lower Manhattan, reported:

The city seemed to have been taken altogether by surprise. The draft had proceeded so quietly during Saturday that no apprehensions were felt. But Sunday morning the storm burst in full fury. Father and I were getting to work … when the ringing of the fire bell and an unusual rise in the streets attracted our attention, and soon after we were startled with the intelligence that the whole of New York had risen against the conscription.

There was almost no military force in the city,… The police and the few soldiers at the barracks were, in nearly every instance, overpowered. Mr. Kennedy, the chief of police, barely escaping with his life. Business was, in a great measure, suspended, and cars and stages ceased running, telegraph wires were out, and anarchy prevailed. The Herald, World, etc. (major newspapers of the day) did everything to inflame the mob, who burned and sacked homes, and attacked negroes and government officials, soldiers or abolitionists.

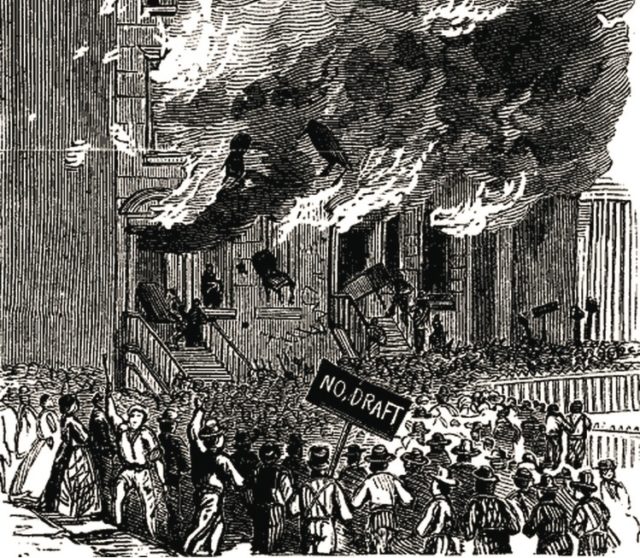

The mob, estimated at 5000 or more, attacked and plundered stores and set them on fire. One of the targets was the New York Tribune, run by ardent abolitionist Horace Greeley.

On Tuesday, July 14, the New York Times reported, “A day of infamy and disgrace. Colored people assaulted. An unoffending black man hung. The colored orphan asylum ransacked and burned.” In addition to targeting blacks, the rioters turned their rage against white abolitionists. Lavinia and her parents feared that the Principia office might be “honored with a call,” but she and her father “went over Tuesday as usual, and got out the paper. We may thank our comparative obscurity, or the failure of the rebels at the Tribune office for our escape.”

On Wednesday, July 15, the New York Times’ headline proclaimed, “The Reign of the Rabble.” By this time rioting had moved to the Williamsburgh area of Brooklyn, where the Goodells lived. The family sheltered at home during the day, taking the name plate off their front door, but by night:

The mob, it was said, were to visit. Mr. Williams came around to inform us that he had heard the church was to be burned, also a large tin factory near us…. We accordingly locked up our house, sent our girl home, took our money and silver, and father and mother went to Mr. Williams’ and I to Mr. Hyde’s…. We sat up till about 12 o’clock, saw a fire over in Brooklyn and heard considerable noise. On waking in the morning we found … our house standing.

New York leaders struggled to contain the riots. Governor Seymour was a Peace Democrat who had openly opposed the draft law and seemed sympathetic to the rioters. New York City’s Republican mayor wired the War Department to send federal troops. By Thursday, July 16, 4000 troops arrived and were able to restore order. Lavinia told her sister, “Last night we staid at home and were not molested…. Comparative quiet is now restored.”

The New York Times’ headline of Friday, July 17 read, “The Riot Subsiding. Triumph of the military.” The published death toll from the riots was 119, but some estimates put the actual number as high as 1200. In addition to the loss of life, the riots cost millions of dollars in property damage and left 3,000 of the city’s black residents homeless. The riots remain the deadliest in U.S. History. NK

Sources consulted: Lavina Goodell’s letter to Maria Frost, July 17, 1863; New York Times, July 13-16, 1863; https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/draft-riots; https://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/317749.html&title=The+New+York+City+Draft+Riots+of+1863&desc=

As a descendant of Goodell and Frost radical abolitionists I am sobered by the level of racism that existed in the North. Little wonder that the end of the Civil War only opened a new chapter in our national complicity in racial discrimination North and South.