Court Cases

It is true that the expectorations of tobacco juice in the Circuit Court sometimes become alarming; but the philosophic woman lawyer reflects that each one of those men, spitting so profusely, probably has a wife at home who is obliged to clean up after him, and inhale the offensive odor, day after day, year in and year out; and in her gratitude that she is not that woman, she readily overlooks the trifling annoyance of sitting in the same room, or even at the same desk with him, a few, brief hours .

Lavinia Goodell, October 1876

Lavinia Goodell practiced law from 1874 until 1880. During that time, she handled a wide variety of cases. She drafted wills and probated estates. She filed claims on behalf of Civil War pensioners. She commenced collection actions and doggedly pursued the debtors throughout Janesville on foot in an effort to collect the money owed her clients. (On one occasion she wrote in her diary, “Got after several men with collections – one of whom treated me to ice cream.” ) Rock County Circuit Court Judge Harmon Conger appointed her to represent a number of criminal defendants. And at a time when judges were very reluctant to grant divorces, she represented at least two women in divorce cases. Fortunately, a number of Lavinia’s court files still exist. Not only do they provide a fascinating glimpse into her law practice, they provide an interesting study of how law was practiced in the 1870s. Here are thumbnail sketches of some of her cases.

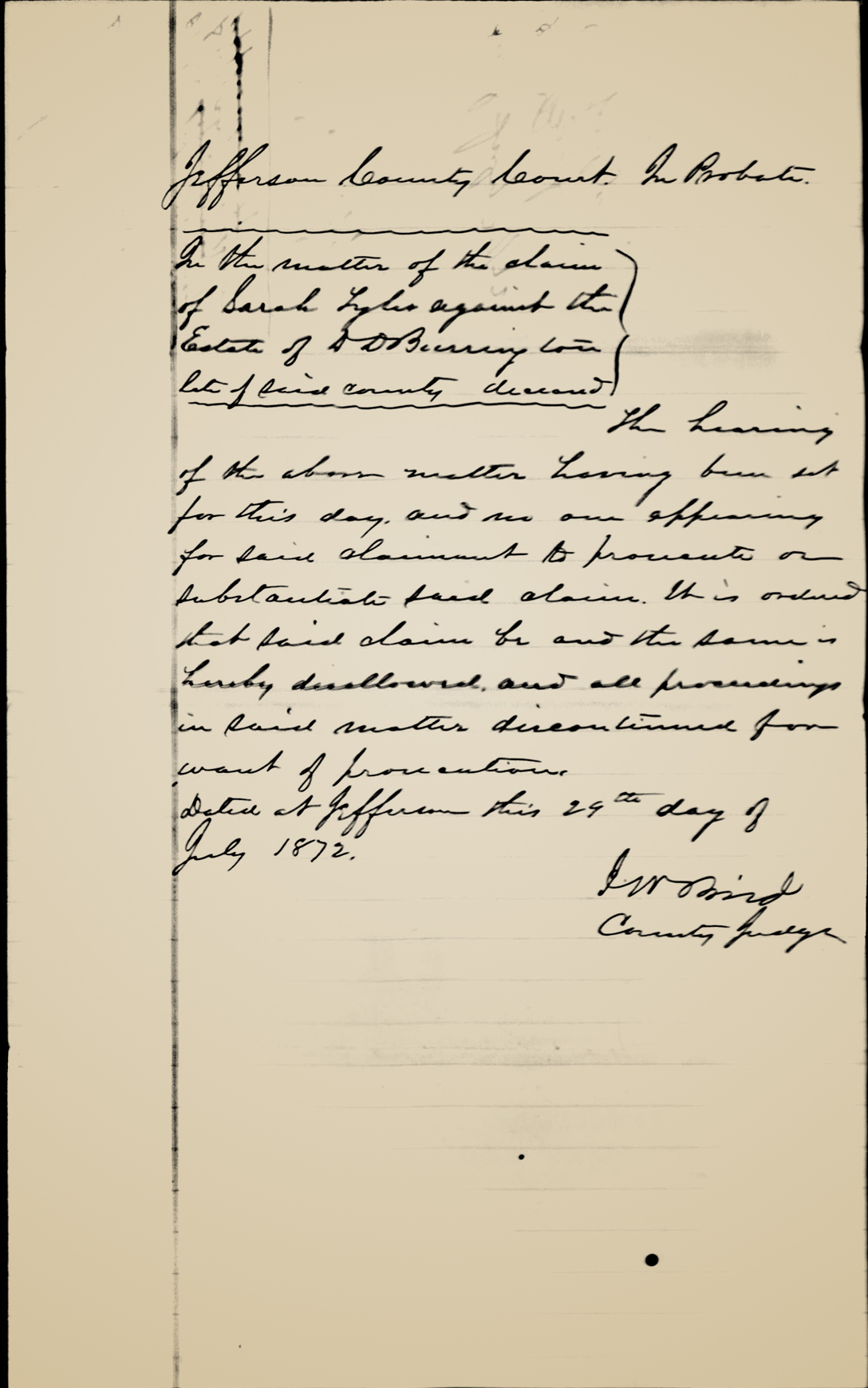

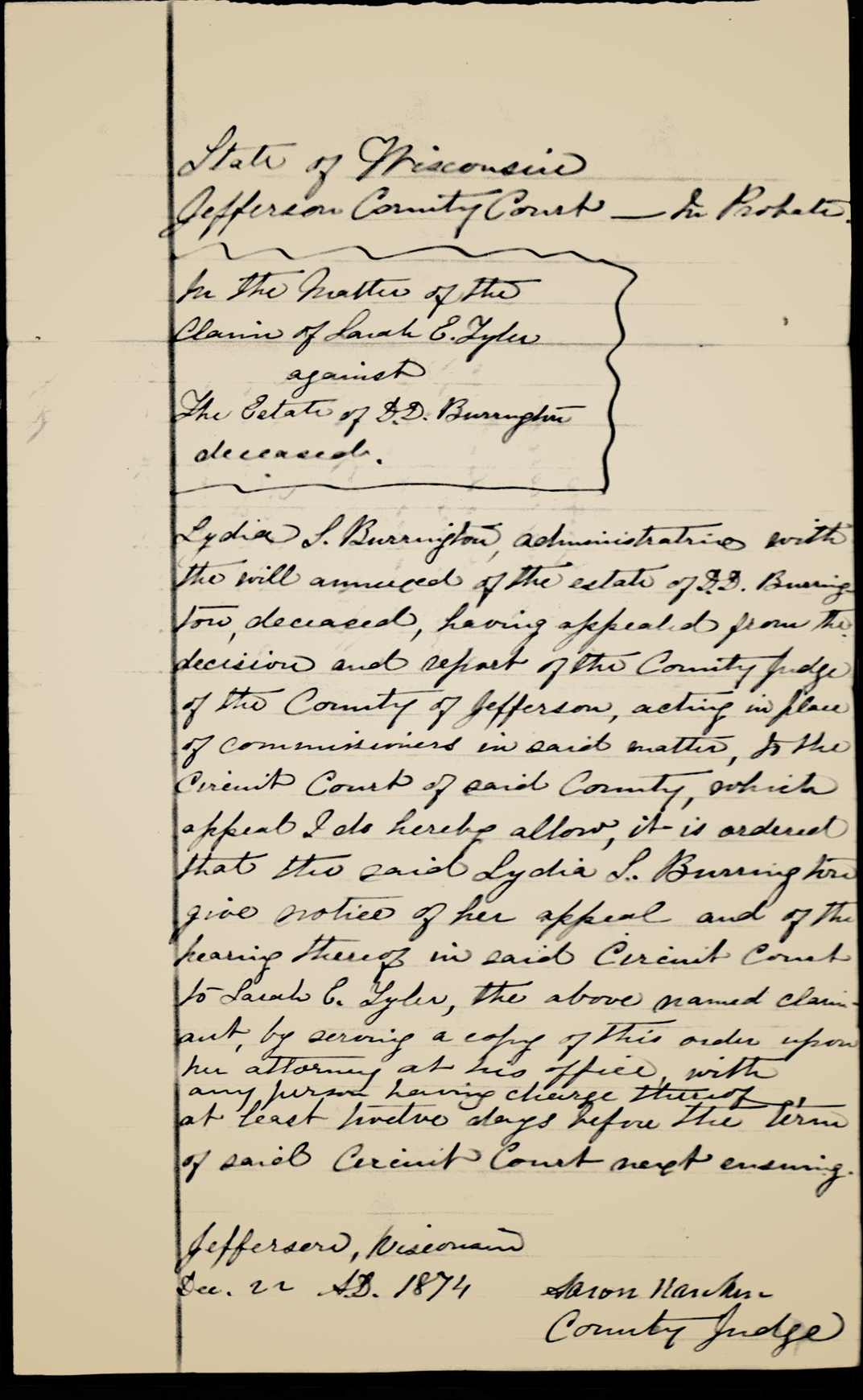

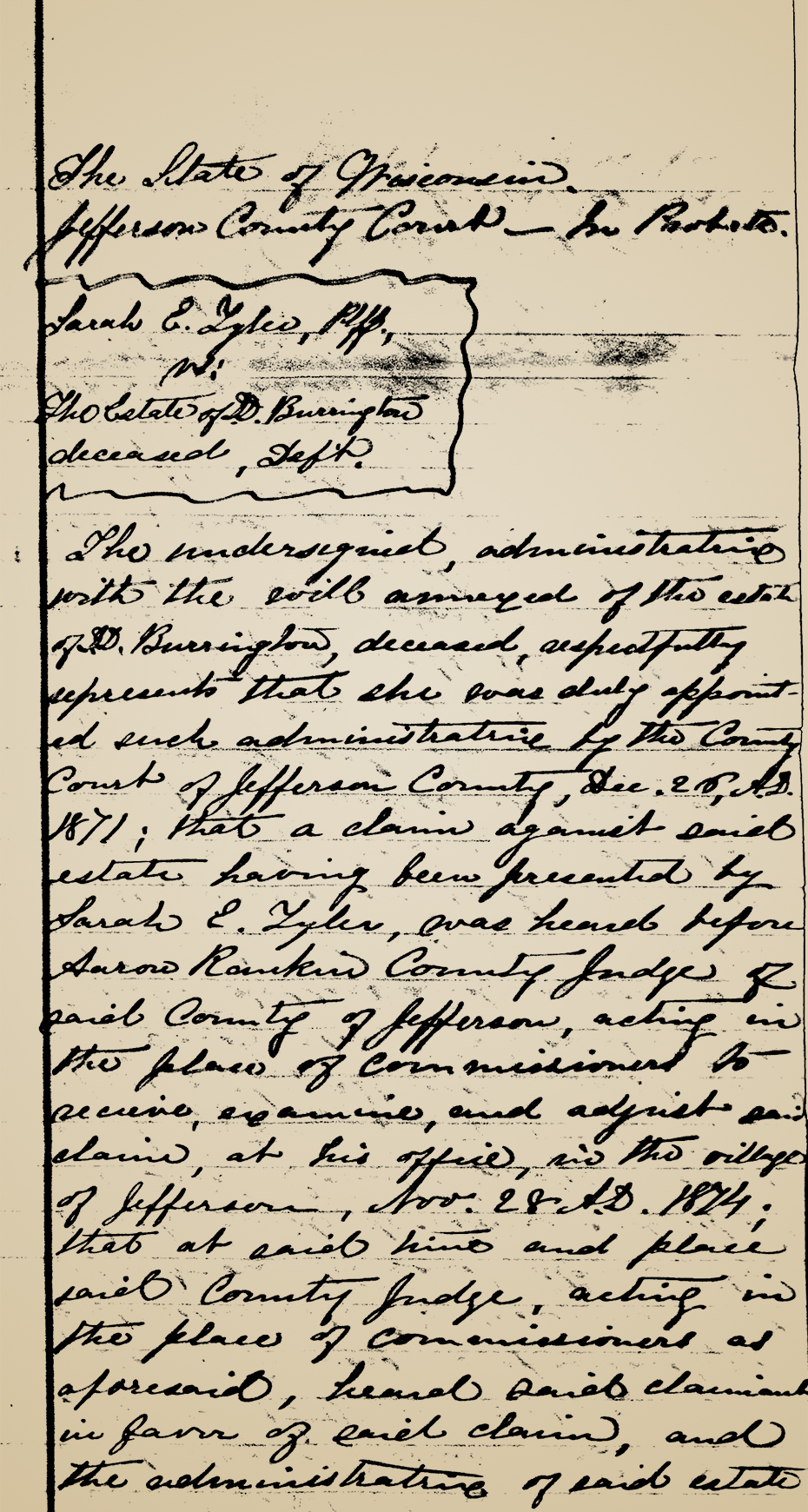

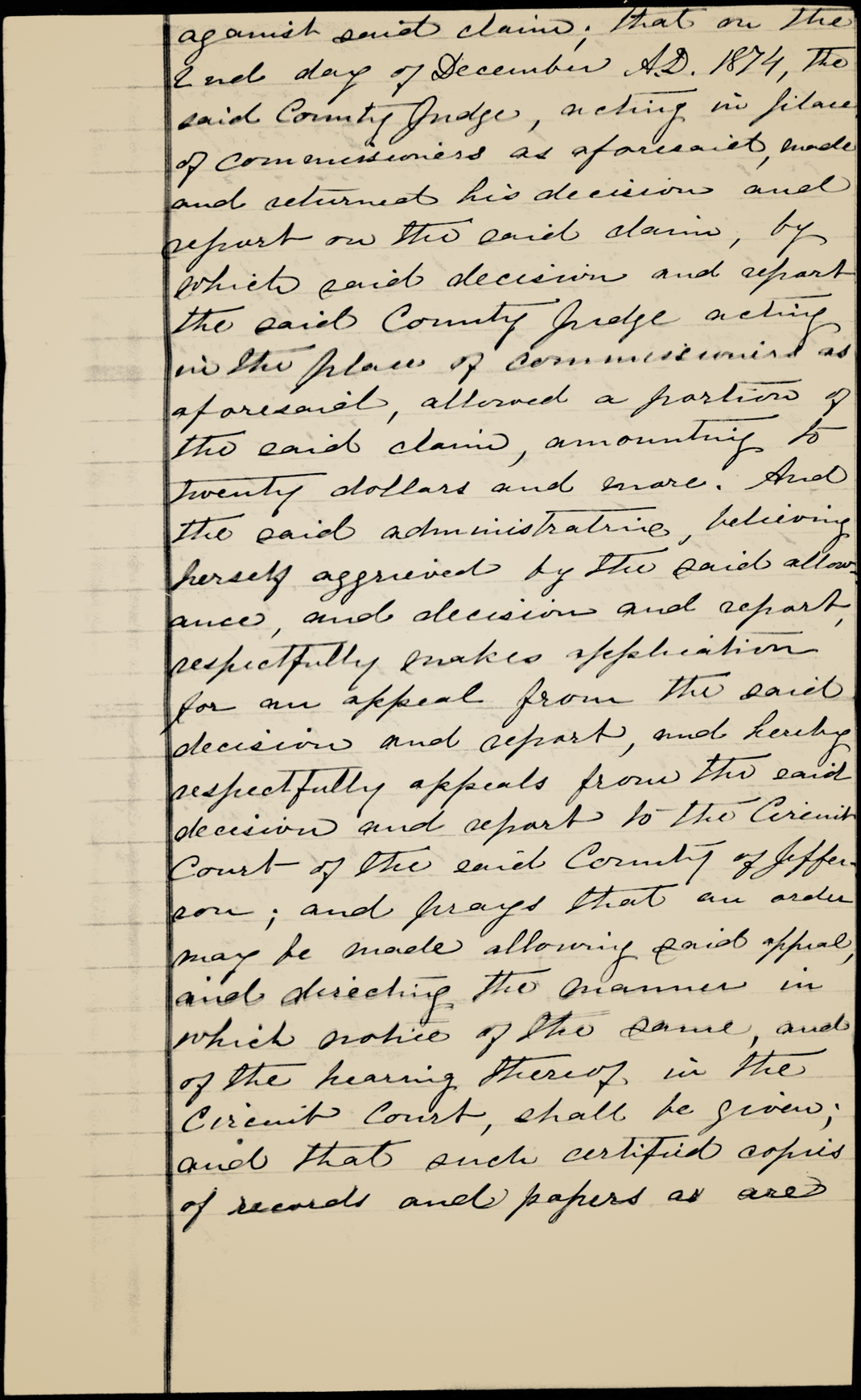

Tyler v. Burrington

This Jefferson County, Wisconsin case involved a claim filed against the estate of Dr. Dennis Burrington. Sarah Tyler, a child from a poor family, had gone to live with the Burringtons when she was fourteen years old and continued living with them most of the time until Dr. Burrington’s death, by which time Tyler was in her early twenties. Tyler claimed that she had rendered services for the Burringtons that were usually performed by servants and that Dr. Burrington had indicated he intended to pay her for her work. The doctor’s widow, Lydia Burrington, countered that Tyler had been treated as a family member, not as a servant; that Tyler had enjoyed good educational advantages while a member of the Burrington household; and that she was entitled to no compensation. The case dragged on for several years. Mrs. Burrington initially hired a male attorney to represent the estate, but after she moved to Janesville, she hired Lavinia to take over the case.

Lavinia tried the suit in county court and, according to her diary entry, enjoyed the experience:

All day and till near midnight trying a case. Lots of fun. I got along first rate; cool and good-natured and made fun of opposing counsel. Think judge sympathized with other side and fear shall lose the case. He has reserved his decision.

Lavinia read the judge correctly. He ruled in favor of Tyler. Lavinia appealed to the circuit court and tried the case to a jury. According to her diary, she thought she would prevail this time:

The thing is in good shape now & we ought to have verdict. The judge gives his charge in morning. There was a big crowd & all seemed interested.

To Lavinia’s disbelief, the jury also found in favor of Tyler. “Jury were out about an hour & bro’t in a verdict for plaintiff. Heaven knows how they could have found it.” Soon after the verdict, Lavinia wrote an article for the Woman’s Journal titled “Women Needed on a Jury.” In it, she expounded on what had gone wrong in the recent trial:

The claimant was young and fair; the widowed defendant was past fifty, faded and plain; the jury were all men…. Few, if any doubt that the superior physical attractiveness of the girl, won her the verdict, and that had the jury been comprised of six women and six men, the decision would have been for the defendant. So say some of the most experienced members of the bar…. The case is to be appealed to the Supreme Court, so the end is not yet.

It was the loss in the Burrington case that started Lavinia on her quest to be admitted to practice before the Wisconsin Supreme Court. When Lavinia’s petition for admission to the Supreme Court was denied, Janesville attorney J.R. Bennett argued the case in her stead. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Mrs. Burrington, finding that Tyler failed to prove that Dr. Burrington expressly agreed to pay her wages. To the end of Lavinia’s life, Mrs. Burrington remained one of her closest friends.

Notice of Appeal and other pleadings from Tyler v. Burrington

Wehle v. Buckingham

Before Lavinia became a lawyer, she was a temperance advocate. She would sometimes visit Janesville saloons and have frank discussions with the proprietors about the harm their establishments were inflicting on local families. On November 1, 1873 she reported, “In afternoon went with Mrs. Guernsey to visit Buckingham’s Saloon and remonstrate with him. Had a rich time.” And on April 29, 1874 she wrote, “Went to morning prayer meeting after which went with Mrs. Baldwin to Buckingham’s Saloon where had pleasant talk with him, but was outrageously insulted by Anson Rogers.” In 1876, Lavinia had occasion to sue W.H. Buckingham, the saloon keeper.

In this Rock County, Wisconsin collection action, Lavinia represented the plaintiffs, three Chicago men who operated a wholesale tobacco business. They had sold 1100 cigars to Buckingham, but he did not pay for them. In a deposition one of Lavinia’s clients stated, “I have been in the tobacco business for the past twenty-two years and think I know the value of cigars…. They were worth all we sold them for.” (Today depositions are either videotaped or a court reporter using a stenograph machine records the entirety of the proceeding verbatim and produces a transcript. In Lavinia’s time, depositions were taken before a notary public and the questions and answers were all recorded by hand. This laborious process resulted in relatively short proceedings.)

Lavinia won a judgment for her clients in justice court in the amount of $71.75 damages and $3.00 costs. Buckingham appealed the judgment to the circuit court, but settled the case before the appeal was heard.

Notice of Deposition from Wehle v. Buckingham

Leavenworth v. Leavenworth

The Leavenworth divorce was probably Lavinia’s most hard fought legal battle and her most disappointing loss. Elizabeth Leavenworth sued her husband Ira for divorce on the ground of cruel and inhuman treatment. The Leavenworths were both in their fifties. Mrs. Leavenworth alleged that her husband had been abusive for many years (Mrs. Leavenworth said her husband had attempted to poison her) and had conveyed their homestead to his brother in order to deprive her of alimony. Lavinia took the case over from another attorney in the summer of 1875. She clearly relished taking discovery. She wrote to her sister:

Last week I went to Columbia County, about 80 miles from here, to attend the taking of some depositions in the new case. Had quite a rich time. The vicious husband was on hand with his lawyer & I had the pleasure of eliciting considerable unwilling testimony from his witnesses on cross examination & getting some good testimony from my own…. Was quite a “lion” in those regions. I was quite hard on the bad husband & expected he would be ready to eat me, but we came back to Janesville together & he was inclined to be quite attentive & devoted. It was very amusing. He actually complimented me on my ability in the management of my case! Perhaps he thinks he can humbug me!

The case culminated in a lengthy trial to the court. According to the Janesville Daily Gazette, “the trial has lasted about a week, and a vast amount of testimony has been taken, amounting to nearly two thousand folios.” Closing arguments in the case were heard on January 25, 1876. The Gazette reported, “Miss Lavinia Goodell made the opening address for the plaintiff this morning, in which she reviewed the testimony and cited numerous authorities. The effort of Miss Goodell added, in the estimation of all who heard her, to the flattering reputation she has made for herself as an advocate at the bar.”

The decision came down on January 29. Judge Conger found insufficient cause to grant Mrs. Leavenworth a divorce. A bitter Lavinia wrote in her diary, “Finished Leavenworth case & lost it. Am too mad to say anymore.” She wrote to her cousin a few days later:

The decision surprised and outraged every unprejudiced person. Judge Conger is notoriously opposed to divorces and never will grant one when he can help it. We thot our case was so strong he couldn’t help it. Of course then she gets no alimony, which was the principal part of the contest…. This has the effect of casting her out into the world penniless in her old age, after working hard & being ill treated all her life & giving her husband all the property – for of course she will never live with him again. It is in effect a decision that a husband may abuse and ill treat his wife all his life, and then turn her adrift in her old age, penniless when he is wealthy, and the courts will sustain him in it. It is as atrocious as the Dred Scott decision. We are awful “mad” and are going to appeal.

Mrs. Leavenworth’s neighbors offered to pay the costs of an appeal, but the parties eventually reached a settlement.

Deposition Transcript for Leavenworth v. Leavenworth

Hathaway v. Hathaway

In the last full year of her life, Lavinia took on another divorce client. Ella Hathaway sought a divorce from her husband Otis on grounds of desertion. The Hathaways were married in May of 1876. According to the complaint, Otis left Ella and their infant daughter in January of 1878. Ella Hathaway further alleged that “the said defendant has not since he so deserted and abandoned this plaintiff … contributed to her support or that of their child … but has neglected to do so, leaving this plaintiff and their said child to be cared for and supported by her friends.” The complaint concluded, “Wherefore this plaintiff prays that the marriage between this plaintiff and the said defendant be dissolved and that she may be awarded the sole custody of her said child, and for such other and further relief as to this court may seem fit and proper.”

Otis’s whereabouts were unknown, so service of the complaint was made upon him by publication in the newspaper.

At a hearing before Judge Conger, Ella testified that since Otis left she and her daughter had been living with Ella’s father. When asked if she had known Otis was going to leave her, Ella answered, “I knew he was going away, but I didn’t know he was going to stay.” Ella offered the following reason why Otis may have decided to absent himself from Janesville in early 1878, “He was running with another woman and I didn’t like it.”

This time Lavinia was able to obtain a divorce for her client. Judge Conger ruled:

[I]t appearing from the proof made … in open court that the allegations made in the complaint herein are true; and the court having found upon proof found ordered judgment to be entered herein in favor of the above named plaintiff for a divorce from the bonds of matrimony between herself and the said defendant; and granting and awarding to said plaintiff the sole custody of her child, the issue of said marriage.

Lavinia noted in her diary, “Two other divorce cases tried the same day and lost. Good for us!”1 Although Judge Conger was “notoriously opposed to divorces,” he could apparently find no reason to require Ella Hathaway to remain wed to a man who had abandoned her.

The Summons for Hathaway v. Hathaway

Sources consulted: “Woman in the Legal Profession,” a paper by Lavinia Goodell read at the Fourth Woman’s Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania October 4-6, 1876, printed in The Woman’s Journal, November 25, 1876; Lavinia Goodell’s diaries; “Women Needed on a Jury,” Woman’s Journal, April 17, 1875;1 Tyler v. Burrington, 39 Wis. 376 (1876); Letter from Lavinia Goodell to Maria Frost, July 10, 1875; Janesville Daily Gazette, January 5 and January 25, 1876; Letter from Lavinia Goodell to Sarah Thomas, February 4, 1876.