“Petition denied.”

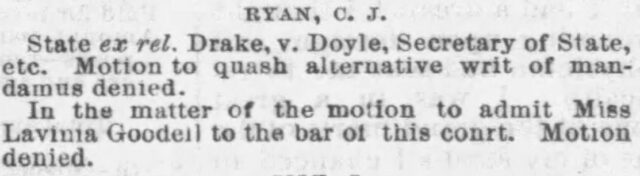

One hundred fifty years ago, the Wisconsin Supreme Court issued one of its most famous – and infamous – decisions. The afternoon edition of the Tuesday, February 15, 1876 Wisconsin State Journal contained a list of the opinions the court had handed down earlier that day. Two of those opinions were written by Chief Justice Edward Ryan. The first was a routine matter: the denial of a writ of mandamus. The second was the denial of Lavinia Goodell’s motion to become the first woman admitted to the bar of the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Although the opinion was authored by Chief Justice Ryan, the other two justices agreed that Wisconsin statutes permitted only men to practice law. In all likelihood, the justices viewed this case as a run-of-the-mill application of the principles of statutory interpretation. Little did they know that their ruling would set in motion a course of events that would forever change the practice of law in Wisconsin.

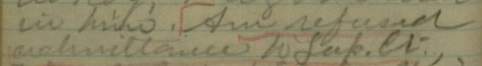

Lavinia learned of the decision the following day and made the terse notation in her diary, “Am refused admittance to Sup. Ct.”

Lavinia had lost this battle and was bitterly disappointed, but she was by no means defeated, and her persistence led, thirteen months later, to a change in the law that specifically stated that no person in Wisconsin may be denied a license to practice law on account of sex. Generations of women lawyers have benefitted from her firm stance against the exclusion of women from the legal profession.

Lavinia’s Supreme Court battle had begun months earlier when she had sought to appeal an adverse decision in a case she had handled in Jefferson County. Any male lawyer admitted to practice in one of the circuit courts of the state was automatically permitted to appear before the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Lavinia assumed the same courtesy would be extended to her but upon consultation with the court’s clerk, she learned that because of her gender she would have to submit a motion asking permission to appear. She drafted the lengthy petition herself but was not permitted to argue it before the court. Instead, she was relegated to sitting in the audience in December 1875 while a male attorney read it on her behalf. A detailed description of Lavinia’s Supreme Court battle may be found here.

The backlash to the Court’s decision was immediate. The day after its release, as Lavinia was first learning about it, the Wisconsin State Journal wrote:

There will be very decided dissenting opinions expressed by members of the bar and by the people respecting the policy of excluding from the bar a citizen over twenty-one years of age, of good moral character, learned in the law, and well qualified to practice, solely on the ground that the applicant is a woman. If her purity is in danger, it would be better to reconstruct the court and bar, than to exclude the women.

It is interesting to note that the Court’s decision was issued at a time when the nation was preparing to celebrate its centennial. In 2026, as we prepare to celebrate the country’s semiquincentennial, the biases Lavinia fought against have not yet been entirely vanquished, but progress continues to be made as each new generation takes up the mantle from the last.

Sources consulted: Wisconsin State Journal (February 15 and 16, 1876); Lavinia Goodell’s diary (February 16, 1876).