Cholera: NYC’s 19th Century COVID-19

As the United States struggles to deal with COVID-19, it may be useful to remember that pandemics are nothing new, nor is the way local governments deal with them. In 1866, while Lavinia Goodell was living in Brooklyn, teaching at a wealthy merchant’s home – (Learn more about her teaching experiences here and here) – cholera claimed the lives of 1137 people in New York City.

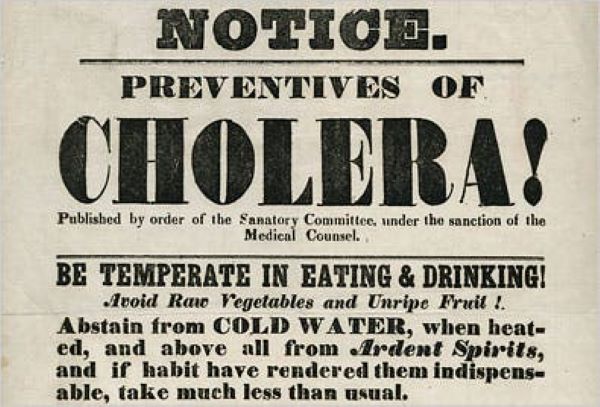

Cholera is caused by bacteria that produces severe diarrhea which can lead to dehydration. As New York’s population grew, sites around the city were littered with cesspools, rotting food and dead carcasses from butcheries. The Board of Health issued orders to clean up sites and urged citizens to engage in better sanitary practices.

New York began bracing for the onslaught of the disease in early 1866. The January 6 New York Times cited the annual report to the Commissioners of Health which was devoted “to a discussion of the cholera question – our prospect of an attack from the plague, the way in which we ought to meet it, and the legislation required in the premises.” By January 27 the Times reported:

The cholera is coming, and its seeds are being sown thick and wide. The great fetid swamp which rests upon our streets is slowly sinking to depths where it will deposit material which, with Summer suns, will rise up to scatter destruction in our homes.

The Times repeatedly called for the Board of Health to act and chastised its members for their sluggishness in responding.

By late April 1866 the disease had reached American shores. Lavinia’s parents were living with her mother’s sister’s family on a farm in Connecticut. Lavinia’s mother tried to persuade her daughter to leave the city and join them in the country:

We see by the Norwich Courier that the cholera has made its appearance at New York. That the Steam Ship Virginia has arrived at the quarantine station in that harbor with as many cases. If the cholera should rage in New York and Williamsburgh we of course should feel very anxious about you and should wish you to be with us, or Maria.

Lavinia’s father offered to send her money if she needed to make a quick getaway from the city. Although Lavinia’s responses to her parents’ letters have not survived, she must have allayed their fears about her well being since her mother wrote on May 12:

I think you take a very sensible view of the cholera. I hope you will as you say, take all due precautions against it. It is a relief that you are in a family that seems to be intelligent on the way and means to preserve health, and are able to carry it out, by having comforts and conveniences suitable for it. We all rejoiced together here, to learn that you had made up your mind to take it easy this summer…. I advise you not to leave off your flannel skirt this summer. If you do leave it off wear flannel over your bowels. I remember people did so when the cholera prevailed in 1832 and it was thought beneficial.

Throughout the summer, the New York Times posted daily updates of the death toll from the disease. Quarantine regulations remained in effect. The District Attorney directed the release of all prisoners in the penitentiary who were confined for “trifling offenses.” Newspapers contained ads for possible cures, including “electro-chemical baths … personally attended by the inventor” and approved by the Academy of Medicine, France. By mid-August the Times reported a decrease in the number of cases and proclaimed, “The enemy being driven out.”

Although criticized for their slow start, the New York Board of Health did initiate actions that limited the spread of the disease. They trained first responders, established an emergency hospital at an Army barracks, and created plans for the disinfection of the city once the cholera outbreak subsided. The Board’s actions established a plan that would be used in future epidemics, and their methodology foreshadowed steps being taken today to combat COVID-19.

Sources consulted: Clarissa Goodell letters to Lavinia Goodell (April 28 & May 12, 1866); William Goodell’s letter to Lavinia Goodell (May 1, 1866); Sarah Thomas letters to Lavinia Goodell (April 27 & May 12, 1866); New York Times (January 6 & 27, April 16, August 6 & 14, 1866);

https://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/disasters/cholera-1866.html; https://www.bbcleaningservice.com/history-cholera-new-york-city.html; https://www.medicinet.com/cholera/article.htm.

Lavinia’s mother’s letter references the family residing in New York during the first Cholera epidemic of 1832 seven years before Lavinia was born. Her father, William Goodell, sent his wife and Lavinia’s sister to live with relatives that summer but remained in the city himself where he was editor of “The Genius of Temperance” and other moral reform publications. He boarded at Sylvester Graham’s boarding house with the Tappan brothers and a young Horace Greeley where he discovered the unbolted “Graham” flour bread served there. For the remainder of his life Goodell adhered to Graham’s teachings foregoing coffee, tea, high seasonings, and meat, though he “never strictly abstained from meat.” (From “In Memorium”).

So interesting!