“A lady who was deaf had cured herself by wearing warm biscuit & butter on her ears.”

Maria Goodell Frost, July 11, 1853

Lavinia Goodell’s sister, Maria Frost, began losing her hearing as a young woman.

Maria’s obituary, published soon after her death on December 31, 1899, said:

[T]he affliction of deafness … began soon after her marriage and gradually increased. For thirty years she heard no public speaking, for twenty years no music, and for ten years she has hardly heard the voices of her nearest friends.

Maria’s letters indicate that her hearing loss was already quite severe in her twenties, and her inability to hear caused her a great deal of distress throughout her adult life. So called miracle cures – and the unscrupulous people who profit from them – are nothing new. Maria pursued a variety of questionable treatments, all unsuccessful.

In 1853, when Maria was twenty-seven years old, she wrote to thank Lavinia for sending her a book, saying, “It has been good company for me more than one otherwise lonely hour. Books are a treasure inestimable to me, as deaf as I am.” A month later, Maria reported trying a new fangled cure for her hearing loss:

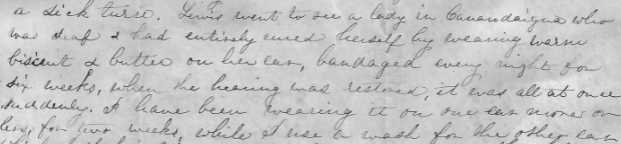

Lewis went to see a lady in Canandaigua who was deaf & had entirely cured herself by wearing warm biscuit & butter on her ears, bandaged every night for six weeks. When the hearing was restored, it was all at once suddenly. I have been wearing it on one ear more or less, for two weeks, while I use a wash for the other ear.

By 1863, Maria considered another new craze to restore her hearing:

I do not know what to do about “Mrs. Brown’s discovery.” I saw her advertisements while I was in New York but took it for a humbug on the very face of it. How I wish I had then known all I now know about it. I would certainly have tried it. Lewis read your letter and has not said a word about it. He does not think there is any hope, I suppose…. Of course Lewis ought to pay for it. I have not asked him. I have only talked about it, and he appears as indifferent as a stone. No doubt if he really thought it would cure me he would be willing to try it. But I think he has given it up & perhaps I ought to give it up and try to be reconciled. Sometimes I think I will, but when I see anyone coming as to call I want to run and hide. I dread it so. The auricles amount to just nothing, people come up to me and see me, and that makes my head about crazy.

The potential cure Maria mentioned was officially known as Mrs. M.G. Brown’s metaphysical discovery.

According to advertisements that appeared in newspapers around the country, for a fee, Mrs. Brown promised to cure blindness, deafness, baldness, and a host of other ailments. While Mrs. Brown had a host of devoted followers, not everyone believed her brash promises. The American Agriculturist magazine ran a series of scathing articles making fun of her claims. Its February 1877 issue chided:

Those who have regarded metaphysics as something intangible are mistaken, for Mrs. B. sells it by the bottle – to be sure at a round price, but it can be bought in the liquid form with a discount to the trade…. The funniest part of it all is that like the Vitapathic man, Mrs. B. has a Metaphysical University – something we never met-afore, though we doubt if any one ever met-a-physician in it.

Maria’s hearing loss caused her social distress. As a pastor’s wife she was expected to call on the women of her husband’s congregation, teach bible classes, and serve on the churches’ ladies’ committees. When she demurred on account of her hearing loss, she was told, “They hoped I would go ahead in it. They did not think the deafness any excuse. They had once had a Methodist minister’s wife here quite as deaf and she was very active.”

While Lavinia was still living in New York and Maria was living in a series of small towns, she sometimes asked Lavinia to purchase ear trumpets or investigate other possible remedies for her:

I have seen advertised some medicines for deafness, not very expensive for sale. 256 Broadway. I do not wish to buy them without further knowledge. With them comes a small brush, the object of which is to cleanse the ear, and soften the membrane. This is given with the medicine or sold alone for thirty cents. I will try to send the money for the brush, and you can get it when you are in that part of the city.

The ear trumpets helped a bit, but none of the other remedies did any good. In 1868, Maria wrote to her parents, “My deafness is no better. I am lonesome. No one tries to have much to say to me except the boys.” Maria’s hearing continued to deteriorate, and as her obituary noted, in the last years of her life she could hear almost nothing.

Sources consulted: Maria Frost’s letters to Lavinia Goodell (June 13, 1853; July 11, 1853; August 30, 1865; April 5, 1870; undated 1876; July 22, 1876); Maria Frost’s letter to her parents (undated, probably 1868); Clarissa Goodell’s letter to Lavinia Goodell (October 1867); Lavinia Goodell’s letter to her parents (May 14, 1871); Maria Goodell Frost obituary, January 1900; American Agriculturist (February 1877); Boston Globe (June 27, 1874).