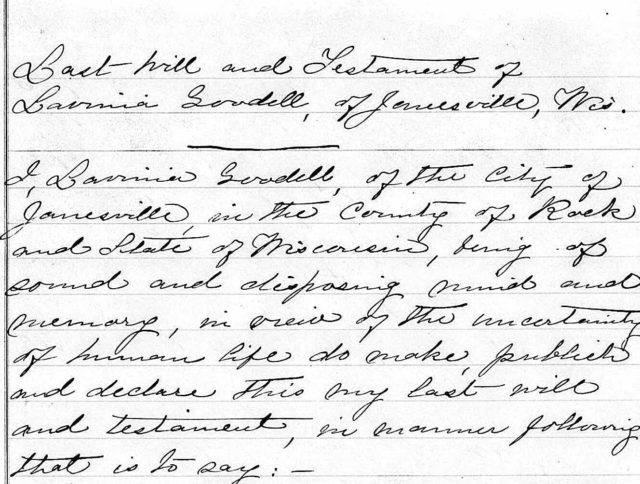

“Lavinia Goodell was insane & not of sound mind or memory.”

Maria Frost’s challenge to Lavinia Goodell’s will, 1880

On April 9, 1880, just nine days after Lavinia Goodell died, one of her executors, Janesville attorney Sanford Hudson, filed an application in Dane County court (although Lavinia had lived in Rock County since 1871 and practiced law there for over five years, she had moved to Madison in November of 1879, making her a Dane County resident at the time of her death) to have her will admitted to probate.

The reason for drafting a will, of course, is to make sure that a person’s estate is distributed in the manner they want, rather than having the property automatically pass to the deceased’s next of kin, which is what generally happens when a person dies intestate. An earlier post discussed Kate Kane’s unsuccessful attempt to collect $50 from Lavinia’s estate. This post will discuss attempts by Lavinia’s sister and eldest nephew to invalidate the entire will.

Continue reading →