“Dear old Beecher! There’s nobody like him!”

Lavinia Goodell, August 30, 1874

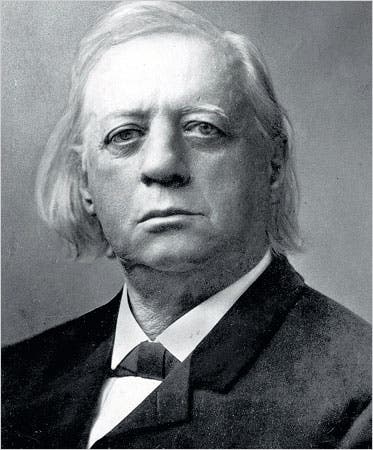

Henry Ward Beecher was one of the most famous men of the nineteenth century. Born in Connecticut in 1813, he was a Congregationalist preacher, a staunch abolitionist, and a supporter of women’s suffrage and temperance. In the early days of the Civil War, Beecher preached anti-slavery sermons from his Brooklyn pulpit. On one occasion a rumor spread that a mob would attack his church, and 200 Metropolitan police officers were dispatched to quell any disturbance that might arise. Fortunately their services were not needed.

Lavinia Goodell’s family held similar political and social views, so it is not surprising that they became acquainted with Beecher when the Goodells were living in New York. Lavinia’s diaries and letters contain many references to Beecher, and reading Beecher’s sermons was a weekly tradition for the Goodells.

The Goodells were not blind followers of any pundit, and while they were generally complimentary of Beecher’s sermons, they sometimes voiced personal criticism of him. In a March 16, 1866 letter, Lavinia’s mother wrote, “We have not yet heard what outrageous thing Mr. Beecher has done. He was always unstable as water. Yet we have thought his sermons rather more solid of late and some of them quite good. We have one of them every Sabbath night.”

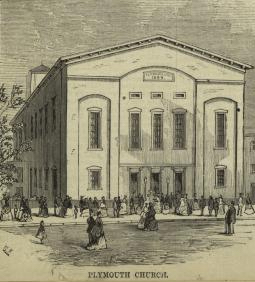

Beecher had accepted a call to Plymouth Church on Orange Street in Brooklyn in 1847 and remained there until his death in 1887. The church building in which Beecher preached still stands.

In the late 1860s when Lavinia Goodell was living in Brooklyn, she sometimes attended his services.

When the Goodells moved to Janesville, Wisconsin, they continued their tradition of reading Beecher’s sermons. They subscribed to the Plymouth Pulpit, a publication containing the sermons, as well as the Christian Union, the weekly newspaper Beecher founded in 1870. The Janesville Gazette carried advertisements for the Christian Union. The ads boasted that the publication “contains the best articles from the foremost writers” and said, “It is a Marvel of Cheapness.” Lavinia thought so highly of Beecher that she hung his engraving in the Goodell’s Janesville parlor.

In the mid 1870s Beecher found himself caught up in a national scandal when he was accused of having an extramarital affair with Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of Beecher’s friend Theodore Tilton. The story first came to light in 1871 when well known feminist Victoria Woodhull wrote about it. Woodhull reported that Mrs. Tilton had confessed the affair to her husband in 1870. The Examining Committee of Plymouth Church declared that Beecher had been the victim of “the most infamous conspiracy known to the present age.” Tilton was expelled from the church.

In 1874, Tilton swore out a complaint against Beecher in Brooklyn City Court, charging him with alienation of his wife’s affections and demanding $100,00 in damages. The trial began in January 1875 and lasted six months, counting recesses when ice on the East River halted ferry traffic, making it impossible for the Manhattan lawyers to get to court.

The press followed the proceedings with the zeal of modern day tabloids. The Janesville Gazette carried almost daily coverage. Lavinia Goodell commented about it frequently in her diaries and letters. She was concerned about Beecher but remained steadfastly in his camp. On July 28, 1874 her diary entry said, “Feel wretchedly about the Beecher business.” On August 14, 1874, “Read [Beecher’s] long statement & believe every word of it.” And on August 16, 1874, “Am in quite a state of bliss now I am relieved of my agony about Beecher.” Lavinia expanded on her feelings in a July 14, 1874 letter to her sister Maria:

I haven’t any fears for Beecher. He will come out all right. They say Tilton is backing down already. I don’t know what ails that fellow. I always heard Mrs. Tilton spoken of in Brooklyn as an unusually active and devoted Christian woman…. She was considered eccentric…. Mr. T. was spoken disparagingly of before I left…. I have no confidence in him.

The Janesville Gazette reported on Beecher’s defense which, not surprisingly, blamed the woman:

Mr. Beecher will acknowledge that, since the beginning of his ministry, he has been beset by letters addressed to him from women, expressing great personal admiration – adoration, indeed – of him as a man and as a minister. He will show that communications of this nature are constantly received by every noted man in the community, and that it is especially the fate of clergymen, poets, and actors, to be the recipients of these abnormal demonstrations from women who are generally diseased physiologically and psychologically.

The trial ended in a hung jury in the summer of 1875 when, after 52 ballots, the jurors were unable to reach agreement. The final vote was 9 to 3 in Beecher’s favor. In 1876, Beecher convened an Advisory Council of Congregational Churches, which found “no substantial ground for believing in the guilt of Mr. Beecher” and resolved that it “regards our brother as worthy of our confidence, and love and express to him our sympathy in the severe trial through which he has passed.” (A fuller account of the Tilton-Beecher saga may be found here.)

Lavinia’s admiration for Beecher continued for the rest of her life. In December 1879, her health failing, Lavinia wrote to Beecher “quoting to him some of his recent utterances about loving the bad into goodness & telling him how myself & others had tried the experiment & asking him if he had any counsel or consolation for us.” On December 20, she wrote in her diary, “Was made happy by a kind letter from Beecher.” In the letter, Beecher wrote:

My dear Madam, Nothing strange has befallen you…. For Christ to live the life of suffering love for others “If ye suffer with me, ye shall also reign with me.” I shall make your letter a text for a talk or a sermon… By the way I knew your father well & honored his ability & fidelity. He shines above as a star. Yours truly, Henry Ward Beecher.

Beecher was true to his word. In one of the last diary entries of Lavinia’s life, on January 17, 1880, she wrote, “Got Chr. Union with Mr. Beecher’s talk on my letter.”

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s diaries; Clarissa Goodell’s letter to Lavinia Goodell (March 16, 1866); Lavinia Goodell’s letters to Maria Frost (June 27, 1873; July 14, 1874); Lavinia Goodell’s letter to Sarah Thomas (December 17, 1879); Henry Ward Beecher’s letter to Lavinia Goodell (December 19, 1879); “The Beecher-Tilton Affair,” The New Yorker (June 12, 1954); Janesville Daily Gazette (December 17, 1860; June 4, 1874; July 29, 1874; November 2, 1876)

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henry-Ward-Beecher; https://connecticuthistory.org/henry-ward-beecher-a-preacher-with-political-clout/;

What a lovely post!