“Don’t try to be a man.”

Maria Frost to Lavinia Goodell, April 13, 1858

In the spring of 1858, shortly before she graduated from the Brooklyn Heights Seminary, Lavinia Goodell was unsure what the next chapter of her life should hold, so she asked her sister for advice, saying:

I must have some life plan. I don’t believe in living to get married, if that comes along in the natural course of events, very well, but to make it virtually my end and aim, to square all my plans to it, and study and learn for no other purpose, does not suit my ideas. … I would be dependent on my own exertions, be firmly established on my own basis. I would study, investigate, try to do good. I would aim at the highest. I think the study of law would be pleasant, but the practice attendant with many embarrassments. Indeed, I fear it would be utterly impractical. Our folks would not hear of my going to college; I should not dare to mention it…. In all probability I must teach, that is all a woman can do.

On April 12, 1858, Maria Frost penned a lengthy response which made it clear she did not look kindly on Lavinia’s aspirations to enter any male dominated profession.

Maria was twelve years Lavinia’s elder and was a wife (married to a minister) and mother. Although her views on women’s rights evolved throughout her lifetime, in the pre-Civil War days she believed women should hew to a traditional path, and she offered her sister specific advice.

First, Maria stressed that Lavinia’s paramount duty was to her aging parents. “I really feel that you owe them so much that you should make no arrangements to interfere with their happiness and that you are in duty bound to stay with them as much as possible.” Next, Maria urged her sister to learn the fine art of housekeeping: “Married or single, rich or poor, you need to know it. … Who who on earth wants a helpless old maid in the family? Our mother would not have one, and I don’t know who would…. You can not make even a reasonable man happy without having to make a home pleasant, neat and comfortable.”

Maria plainly hoped that her sister would eventually marry. She said, “If you should have a truly good opportunity to marry any time after the age of twenty I should think it would be for your greatest good.” And, “A family fireside is the sweetest place on earth. Sorry minded am I, for those who cannot taste its blessedness in their own home, after friends of infancy and children have passed away. No true woman can have the wants of her nature truly met, without becoming a mother.”

Finally, Maria threw cold water on Lavinia’s dream of practicing law or embarking on any career outside the conventional sphere established for women. While Maria considered teaching an acceptable career choice for a woman – for a short time until a suitable husband could be found – and she encouraged Lavinia to write, she was adamant that her sister not think about any loftier career goals:

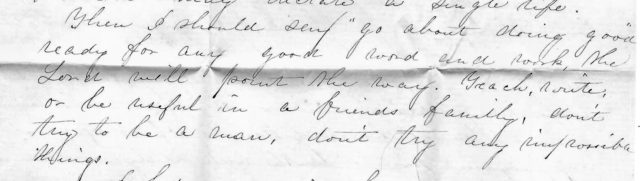

The ideas you entertained last summer I hope you have exploded long long ago. If you value your own happiness do not take that course. It should be a loud call of duty, and nothing less, that could induce any woman to strike out a new and untried path. God has not called you to that profession I know. He has given you reason. Do not pervert it. … The Lord will point the way. Teach, write, or be useful in a friend’s family. Don’t try to be a man, don’t try any impossible things.

Lavinia responded by saying that she agreed that her first duty was to her parents, and that she needed to learn housekeeping. However, she defended her interest in eventually becoming a lawyer:

If I took the course I spoke of last summer it would be with full knowledge and feeling that I was sacrificing much personal happiness. I think it is a simple desire to do good that has led me to think of it. It would be very hard to bear the reproach of dear friends. Still if I can feel it to be my duty, I hope I shall perform it unflinchingly. What is more womanly than the desire to defend and protect the widow and the fatherless and in a field where they have been wronged hitherto? Any affectation of manliness I should despise. Cannot true womanly refinement be maintained in such a position? Still it is too important a matter to decide hastily. I shall wait eight or ten years and see how matters stand.

When Lavinia began studying law fourteen years later, she was thirty-three years old and had already had a successful career as a teacher and an editor. If Maria Frost continued to harbor misgivings about her sister’s career choice at that point, there is no record of it, and when Lavinia shared the happy news in June 1874 that she had been admitted to the bar, Maria immediately responded with hearty congratulations.

Sources consulted: Maria Frost’s letter to Lavinia Goodell (April 13, 1858); Life of Lavinia Goodell, unpublished biography by Maria G. Frost, from the William Goodell Family Papers at the Special Collections & Archives, Berea College, Berea, Kentucky.