Lavinia’s jail school

“I had no idea that criminals were so interesting,” Lavinia Goodell told her sister, Maria. “I believe I could run [the Rock County] jail, so as to turn out every man better than he came in. Jails and prisons could just as well be made schools of virtue as vice if people chose to have it so, and would give a very little thought to the subject.” For the last four years of her life, while her elderly parents were failing and she was suffering a fatal illness, Lavinia poured herself into reforming criminals.

She started with prayer meeting, an experiment she wrote about for the Christian Union. She and some friends, “enthusiastic workers of the Young Men’s Christian Association,” told the sheriff that they wanted to hold weekly prayer meetings with the prisoners. He considered the project as futile as sending a delegation “to the infernal regions to convert his Satanic majesty.” Still, he gave his consent.

By this time, Lavinia had been to the jail many times for client visits; the others had not. As they approached, they heard shouts, screams, “roisterly singing,” and coarse jokes. The jail seemed like “a den of wild beasts.” It had two rooms full of prisoners. Lavinia’s band entered one and found it redolent of tobacco, “the floor covered with expectorations of that seductive weed” and soiled playing cards. The prisoners were disheveled and dirty.

The band approached each man, shook his hand, and spoke kindly to him. They announced that they were holding a prayer meeting and began singing hymns like “Hold the Fort” and “Ninety and Nine.” Afterwards, each volunteer spoke a few words about the love of Christ and the joy of following in his footsteps. Then they all knelt on the filthy floor and began to pray.

You can imagine how this went over. Some of the inmates laughed themselves silly. The wall dividing the two rooms had a small opening allowing inmates to converse. The inmates in the other half of the jail discovered the prayer meeting in progress and started shouting and singing “wild snatches of coarse songs.” The volunteers finished their meeting, again shook hands with each prisoner, and left them with papers and magazines to read.

The next week Lavinia’s band repeated the same experiment on the other side of the jail and received the same reaction. They continued week after week. After a while, the inmates started cleaning the floors and tidying themselves before the prayer meetings. Those in the other half of the jail gathered quietly around the hole in the wall to listen. James Tolan, Lavinia’s young watch thief, told her that the inmates looked forward to the weekly visits, and they liked the singing best of all.

While Lavinia hoped these men would eventually lead good Christian lives, she also wanted them to become productive members of society upon their release. To this end, she started reading the State of Wisconsin’s reports on prisons and jails. She met and corresponded with the chaplain for Wisconsin’s prisons. She also read George Thompson’s “Prison Life and Reflections.” She formulated ideas for helping inmates but, just as important, for getting the community involved and setting an example for other prisons.

During her early twenties, Lavinia taught school in New York City. She applied those skills to her new students: burglars, horse thieves, whiskey robbers. She found several them to be highly intelligent and eager for more mental stimulation, so she taught classes in math, literature, and composition. She persuaded friends and her cousin, Sarah, to help with the teaching.

Then she started a lecture series for the jail. She and Janesville dignitaries gave a series of nine lectures on subjects such as the science of government, temperance, the formation of character, the use of words, and money. The inmates loved it.

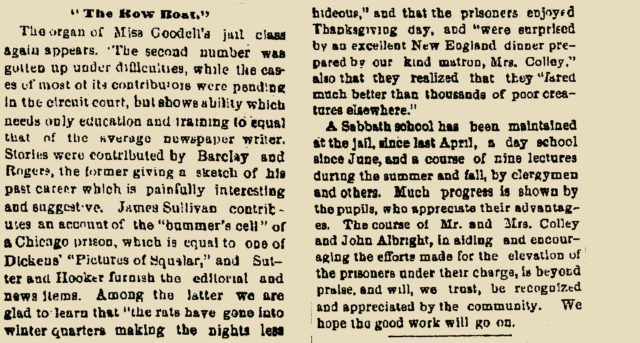

Lavinia also invited prisoners to write their autobiographies, which she reviewed and edited. This project inspired the publication of “The Row Boat,” a collection of stories by the Rock County Jail inmates. Lavinia reported on the jail newspaper in the December 5, 1877 Janesville Gazette. Barclay gave a “painfully interesting and suggestive” sketch of his past career as a horse thief. Sullivan described the “bummer’s cell” in a Chicago prison equal to Dickens’ “Picture of Squalor.” An inmate assigned to give an update for the Rock County Jail reported that “the rats have gone into winter quarters making the nights less hideous” and that on Thanksgiving Day the jail matron surprised them all with a New England dinner. They considered themselves lucky, as prisoners go.

Lavinia found this work enormously gratifying. She told her sister that when prisoners thanked her for showing interest in them, it motivated her to work even harder. “I never should have had all of this experience with criminals, she wrote, if I had not become a lawyer. It has opened quite a new field of thought to me.” CB

Sources consulted: Maria Goodell Frost, Life of Lavinia Goodell, (unpublished manuscript at Berea College); Lavinia’s letters to Maria December, 1875 and March 30, 1876; Lavinia Goodell’s Diaries 1/19-21, 2/18-19, 4-18-21, 1876; 6/19/1877; Lavinia Goodell, “Prayer Meetings in Jail,” Christian Union, May 31, 1876; Lavinia Goodell, “The Row Boat,” Janesville Gazette, Dec. 5, 1877.

This is illuminating. While I knew of Lavinia’s involvement with “her boys” and the “Row Boat”, it had escaped me that she had enlisted other members of the community to participate in her reform project or that it had attracted favorable public attention. Obviously, Dickens had inspired her to make a difference.