Spittoon or no spittoon? Hanging out a shingle in 1874

If launching your own law firm seems daunting today, imagine what it was like for Wisconsin’s first woman lawyer in 1874. Lavinia’s letters and diaries describe how she established her practice and planned to get work. Some parts of the process are much the same as today; others are amusingly different. For example, when furnishing her office Lavinia pondered “spittoon or no spittoon?” If her prospective clients had “spitting propensities” they would expect one.

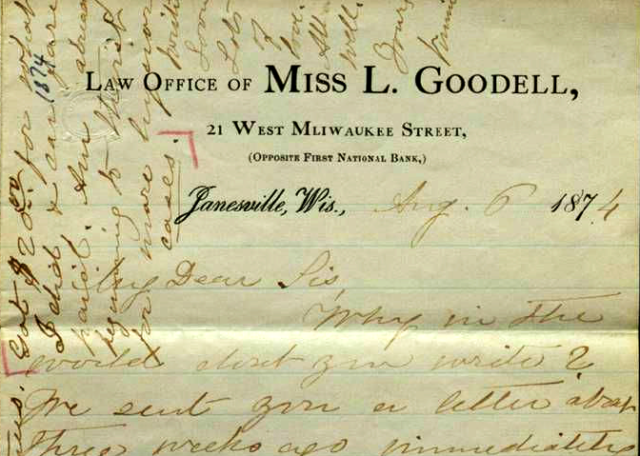

Upon admission to the bar, Lavinia’s first order of business was to order business cards. Her Facebook page (which we hope you’ll “like“) features her business card from 1879 when she practiced law in Madison. It states simply: “Lavinia Goodell, Attorney at Law.” But her cards from June 1874 when she became one of just a few women lawyers in the nation–were different. We don’t have a sample to show, but she proudly explains what made them distinctive:

I put “Miss” on my cards because I am tired of getting letters directed to Mrs. Lavinia Goodell, and having to explain, also because my name, being rather unusual, some benighted heathen might not know, but what I was a man, and I want everybody to have a realizing sense that I am a woman lawyer. Besides, I do not think it is necessary to do everything just as men do, if you know a better way.

Lavinia began as a solo practitioner. This was not by choice. Although she read law at home by herself, she had, with her father’s help, entered a special arrangement with an attorney named A.A. Jackson whom she described as “one of the pillars of the Cong. Church and a good woman’s rights man.” She regularly met with Jackson for reciting and tutoring. In recompense, she worked for him for free. Jackson practiced law with Pliny Norcross, the attorney who had moved for her bar admission. Given these relationships, Lavinia had hoped to join their firm. Norcross said “yes,” but Jackson, for unknown reasons, said “no.”

Undeterred, Lavinia consulted other lawyers on how to start a practice. One actively discouraged her from opening her own office. “That encouraged me the most of anything yet,” she told her cousin. She shrewdly decided to rent a small back office on the same floor as Jackson & Norcross with the hope of receiving contract work from them, consulting them on cases, and using their library.

Launching a solo practice requires capital. Lavinia, a skillful money manager (more on that later) had $1,100 invested but not much in liquid assets. She borrowed money from her sister, Maria, at 10% interest in order to pay rent and purchase furniture and books. Gerrit Smith, a leading 19th Century American abolitionist, social reformer, politician and dear family friend, sent her $20 toward her new library. She records paying “$33 1/3 per annum” in rent, $70 for law books, and $10 for one desk. Her $479 startup costs for one year equal $10,830 in 2020 dollars. Interestingly, The Lawyerist reports this as the approximate cost of starting your own law practice today.

What did the office of Wisconsin’s first woman lawyer look like? We know from one of Lavinia’s letters to Maria:

My office is prettily furnished, and everybody says looks pleasant. I have a pink straw matting on the floor, the one that was in my bedroom last summer, turned the other side up. Mr. Hoppin’s desk varnished up, a carpet lounge, two rocking and three armchairs, a table on which reposes my small library, and in the closet, a mirror, washstand, toilet articles . . .

I debated much with myself as to whether I should furnish a spittoon for the use of my future clients. I never saw a law office without one. Still I do dislike to mar my pretty room with such an unsightly object. So I conclude to wait and see whether my clients develop spitting propensities.

About clients. Just 10 days into her practice, Lavinia received her first bit of legal work for a Mr. Hunt for one dollar. “My first fee,” she wrote in her diary. “Felt quite encouraged.” She exhorted Maria (then living in Michigan): “I do hope I shall get lots of clients. Show my cards around. Perhaps there is somebody there who wants to get divorced, or sue somebody, or foreclose a mortgage in this county!”

Two weeks later, still “intoxicated” from her recent successes, Lavinia imagined her future cases:

I am looking forward to the time when compartments labeled “Civil cases,” “Criminal cases,” “Accounts,” etc. will be filled, yes, crammed with formidable looking documents . . .

I wonder what my first case will be! A foreclosure, a divorce, an ejectment, assumpsit, or what? Blackstone is said to have waited four years for his first case, so I shall be consoled if I do not get one at once.

Within weeks Lavinia bested William Blackstone! To learn more about her first two trials and life as Wisconsin’s first woman lawyer, subscribe to this blog by email, Facebook or Twitter. Also, tell us what you think about the launch of Lavinia’s law practice. CB

Sources Consulted: Maria Goodell Frost, Life of Lavinia Goodell (unpublished manuscript); Lavinia Goodell’s Diary, June 27, 1874; Lavinia’s letter to Sarah Thomas, March 7, 1872; Lavinia’s letters to Maria Frost, June 22, June 30, and July 14, 1874.