“Wasn’t Gerrit Smith a dashing good creature?”

Lavinia Goodell, November 7, 1861

Gerrit Smith was a prominent abolitionist and social reformer who was a longtime acquaintance of Lavinia’s father, William Goodell. The Goodell family remained friends with Smith for the rest of his life, and Smith was one of Lavinia’s mentors.

Smith was born in Utica, New York in 1797. (Lavinia Goodell was born in Utica in 1839.) Smith’s father was an early partner of John Jacob Astor in the fur trade. Shortly after Smith’s father died in 1837, a financial crisis led to a depression that lasted into the 1840s. Banks would not provide Smith with the loans he needed to meet his business obligations, so he turned to his father’s old partner for help. Astor loaned Smith $250,000 in return for a mortgage on property for which Smith had paid $14,000 ten years earlier. Due to a mixup, there was a delay in sending the mortgage to Astor, so for several weeks Astor had nothing but Smith’s word to secure the $250,000 loan.

According to the New York Times lengthy obituary, Smith was a “great stockholder in that peculiar institution known as the Underground Railroad.” His estate was on the direct route to the Canadian border, and his house was always a welcome station. He also furnished money for legal expenses of persons charged with infractions of the Fugitive Slave Law. Smith was very close to John Brown and supplied him with funds, but Smith apparently did not know some of the money would be used to incite a slave insurrection in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia in 1859.

In the 1840s, Smith played an active role in the founding of the Liberty party, which was an early advocate of the abolitionist cause. In 1860, Smith vied with William Goodell for the party’s nomination for the presidency, with Smith being the victor. Smith was also a long time acquaintance of Harriet Tubman.

In late 1861, in the early days of the Civil War, Lavinia Goodell spent several days at Smith’s home. Twenty-two year old Lavinia came from a home of modest means but was very well read and was always in the market for new reading material. She found the Smith home entrancing. She wrote to her sister Maria:

How delightfully they all live there, and how beautiful and tasty is every surrounding! And the books, and the pleasant society and conversation!. O, I can’t begin to tell you how I enjoyed it! It is so refreshing to meet and enjoy such a noble, glorious experience of manhood as G.S. … He gave me vols. of his speeches and sermons, and $5 to spend in books as a present from him. I am in ecstasies and have been making my selections…. Isn’t it grand, and wasn’t he a dashing good creature?

Upon returning home, Lavinia’s friend Mary Booth offered advice on where to purchase books at a good price.

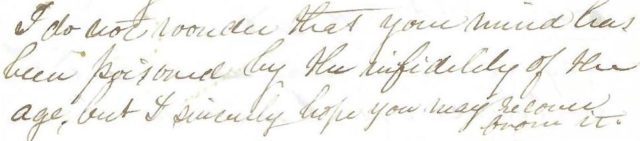

Lavinia’s father was not always in lockstep with Smith’s political beliefs and occasionally wrote spirited articles countering something Smith had written. Lavinia’s sister, Maria Frost, found some of Smith’s religious views much too liberal. In 1866, when Lavinia was teaching in Brooklyn, Maria indignantly wrote, ” Gerrit Smith told Miss Holley that you agreed with him exactly in theology…. I am perfectly shocked…. The poor man has no found action to rest a hope of eternal life upon…. Unless Mr. Smith’s eyes are opened there will be a great disappointment for him in another world.” Maria, a pastor’s wife who lived in upstate New York, concluded her letter by saying, “I do not wonder that your mind has been poisoned by the infidelity of the age, but I sincerely hope you may recover from it.”

We do not have Lavinia’s response, but there is no indication that her sister’s views in any way dimmed her admiration for Smith. When Lavinia was admitted to practice law in the summer of 1874, Gerrit Smith recognized the accomplishment by sending Lavinia a congratulatory letter and a check for $20 as a contribution toward her library.

When Smith died six months later, the New York Times devoted many columns to eulogizing him. It said:

His mind was incapable of occupying any middle ground, or of qualifying its conclusions. Slavery must be either right or wrong. If it was wrong, then it must be done away with, and that promptly. It was wrong to get intoxicated, therefore it was wrong to allow the sale of intoxicating liquors. All human beings were equal in rights; therefore women should vote. War was murder, and murder was a crime against God and humanity; therefore war was necessarily wholly evil (though it should be said that he modified his opposition to war when it became necessary as a means of emancipation.)

He believed heartily and logically in the brotherhood of the human race. As an abstract proposition he accepted it with great earnestness, and as a practical truth he felt it deeply and acted upon it with peculiar warmth and fidelity. His great wealth was constantly bestowed to relieve suffering or to aid in any movement that he believed would improve the condition of any class…. To him half a loaf was a great deal worse than no bread. He believed profoundly in the moral character of political questions, and in morals he was uncompromising.

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s letters to Maria Frost (November 7, 1861; July 14, 1874); Maria Frost’s letter to Lavinia Goodell (January 31, 1866); New York Times, December 29, 1874; https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gerrit-Smith; Harriet H. Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (W. J. Moses, printer, 1869).

After moving to Janesville, Lavinia delayed joining a church. She fretted about finding one where her religious views would be accommodated. Eventually, she did join the Congregational Church where her mother and father worshiped. She became close to the Minister there and used the church as a foundation for many of her intellectual and social reform pursuits.