“We would have every path laid open to woman as freely as to man.”

Margaret Fuller, 1845

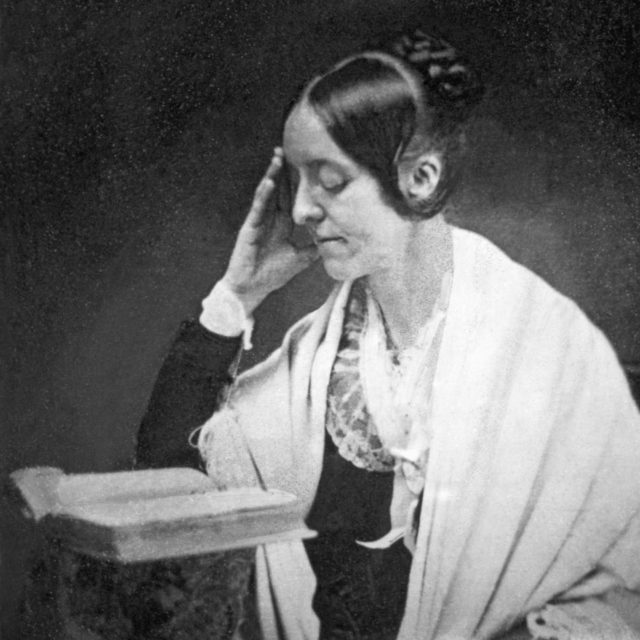

Although Margaret Fuller may not widely known today, in the mid-nineteenth century she was a well known teacher, editor, and essayist whose best known book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, published in 1845, examined the place of women within society. Lavinia Goodell admired Margaret Fuller’s works and spent countless hours reading them in order to prepare a paper that she delivered at a December 1877 meeting of Janesville, Wisconsin’s literary society, the Mutual Improvement Club.

Margaret Fuller was born in Massachusetts in 1810. A precocious child, her father, a lawyer, oversaw her education, providing his daughter with tutors in Latin, philosophy, history, science, literature, and German. After her father’s death in 1835, the family found itself quite poor, and Margaret went to Boston as a teacher. She taught in Bronson Alcott’s school and offered classes for young ladies. She became a friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson and other Transcendentalists. Few would accuse her of being overly modest. It was while dining at Emerson’s home that Margaret uttered what is probably her best remembered remark: “I now know all the people worth knowing in America, and I find no intellect comparable with my own.”

Emerson said of his conversations with her:

They interested me in every manner, — talent, memory, wit, stern introspection, poetic play, religion, the finest personal feeling, the aspects of the future, each followed each in full activity. She knew how to concentrate into racy phrases the essential truth gathered from wide research and distilled with patient toil, and by skillful treatment she could make green again the wastes of commonplace.

Starting in 1839, Margaret organized a series of “conversations” for women in Elizabeth Peabody’s bookstore in Boston. Between 1840 and 1844, the Transcendentalists published their Journal The Dial in four volumes. Margaret was the first editor. (She rejected one of the essays submitted by Henry David Thoreau.) She also wrote poetry, reviews, and critiques.

In 1844,Margaret moved to New York to become a contributor for Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. In 1845, Greeley published Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century, an expanded version of the essay “The Great Lawsuit” originally published in The Dial in 1843. The book was an important feminist document because it called for equality in marriage and in all other spheres. Margaret rejected the notion that women should settle for domesticity, saying “Let them be sea captains, if they will.” She wrote:

The civilized world is still in a transition state about marriage; not only in practice, but in thought. It is idle to speak with contempt of the nations where polygamy is an institution, or seraglios a custom, when practices far more debasing haunt, well nigh fill, every city and every town. And so far as union of one with one is believed to be the only pure form of marriage, a great majority of societies and individuals are still doubtful whether the earthly bond must be a meeting of souls, or only supposes a contract of convenience and utility.

In 1846, Margaret went abroad. She reported on her travels for the Tribune. In Italy, she married an impoverished Italian nobleman ten years her junior, Giovanni Angelo, Marchese Ossoli, and had a son. In Florence, she wrote a history of the Italian revolution. In the summer of 1850, with her husband and son, she sailed for the United States. The ship’s captain died of smallpox en route. With an inexperienced captain in charge, the ship was wrecked while in sight of land off Fire Island, New York. Margaret’s body was never found. Her manuscript about the revolution was also lost.

Upon hearing the news of her death, the Tribune sent one of its editors to the scene of the wreck to help recover bodies. The paper published a heartfelt tribute:

A great soul has passed from this mortal stage of being in the death of Sarah Margaret Fuller…. America has produced no woman who in mental endowments and acquirements has surpassed Margaret Fuller, and it will be a public misfortune if her thoughts are not promptly and acceptably embodied.

Sources consulted: Margaret Fuller, Woman in the Nineteenth Century (Greeley & McElrath 1845); Our Famous Women (A.D. Worthington & Co., Publishers 1885); Megan Marshall, “On Margaret Fuller and Woman in the Twenty-first Century,” (The New Yorker November 15, 2016); New York Tribune (July 23, 1850).