“You had become a person in the eyes of the Wis. Supreme Court.”

Emma Brown letter to Lavinia Goodell, July 11, 1879

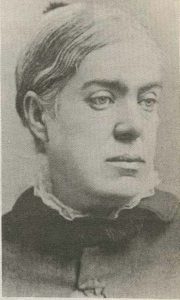

Emma Brown, publisher of the Wisconsin Chief temperance newspaper, helped give Lavinia Goodell’s nascent legal career a boost in the summer of 1874.

Emma was born in Auburn, New York in 1827.

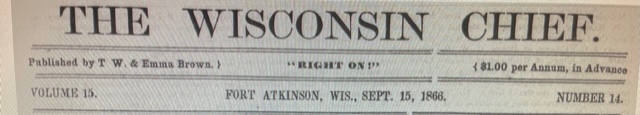

In 1849, Emma and her brother, Thurlow W. Brown, became co-publishers and co-editors of the Cayuga Chief, a temperance newspaper. By 1857, the Browns had relocated to Wisconsin, purchased assets of a defunct Jefferson newspaper and renamed their paper the Wisconsin Chief. Emma Brown supplemented their income by operating a printing shop.

Thurlow Brown was a sought after speaker, and the Chief reprinted many of his speeches. Emma rarely signed her contributions to the paper. When Thurlow died in 1866, few expected the Chief to survive, but Emma Brown not only soldiered on, she made the paper her own and began to use it to promote women’s rights.

It is unknown when Lavinia Goodell first met Emma Brown, but Emma reported meeting Lavinia’s father, William Goodell, as a child in the late 1830s when her family attended a temperance event in New York state. We also know that the Goodells read the Chief. When Lavinia helped organize a chapter of the Ladies Temperance Movement in Janesville in the summer of 1873, she enlisted her father to write a lengthy letter to the editor that was published in the August 23 issue of the Chief. William Goodell boasted about his daughter and her fellow temperance warriors:

Thus it was that the ladies of Janesville felt impelled to come to the rescue, the gentlemen being too busy; some of them, perhaps, too timorous, or too apprehensive of detriment to personal interests, to interfere in such a dubious contest. Be this as it may, the ladies found time, and lacked not courage, resolution, or perseverance, to meet the exigencies of the crisis.

The following summer, soon after Lavinia was admitted to the bar, women temperance advocates in Jefferson County hired Lavinia to prosecute two cases for selling liquor on Sundays. (Read more about the cases here and here.) Although Emma’s precise role in hiring Lavinia is not known, Lavinia’s letters and diaries indicate that Emma participated in pre-trial meetings with Lavinia, and the Chief ran commentary about the cases. After Lavinia persuaded a justice of the peace to find the two saloon keepers guilty, the men appealed and demanded jury trials. Lavinia won one of the jury trials and lost the other but later learned that the jury had deliberated for six hours and the vote stood nine to three for a verdict of guilty. Lavinia wrote to her sister, “And the saloonkeeper was so discouraged that he gave up his business, so you see it was a moral victory after all.”

Soon after the verdicts were returned, the Chief ran an article lamenting the lack of a conviction in the second case. The Chief said, “the proof was plain and positive as to the violation of law” and “it is believed the defendant was quite as much astonished at the rendering [of a not guilty verdict] as the prosecution.” The article lauded Lavinia’s work on the case, saying, “The ladies who had these prosecutions … employed Miss Goodell, of Janesville, as counsel, and were much pleased with her tact and ability in managing the suits.”

Unfortunately, Lavinia’s pride in successfully handling the cases was dimmed a few weeks later when one of her clients complained about the fee. She wrote in her diary, “A letter from client in which she speaks grudgingly of my fees and it has quite disheartened me. Don’t feel like ever doing anything – I work so hard and get so little and even that is grudged me.”

But by all accounts, Lavinia and Emma Brown remained on good terms for the rest of Lavinia’s life. Lavinia’s diaries and letters mention meeting Emma on a number of occasions. In 1879, Lavinia sent Emma the lengthy “In Memoriam” booklet honoring her father, who had died in 1878. Emma wrote to Lavinia thanking her for the booklet. She closed by saying: “I meant to have said in the Chief that you had become a “person” in the eyes of the Wis. Su. Court but overlooked it. One my exchanges attributes Judge Ryan’s illness to your furtherance in insisting on your rights.”

Lavinia died less than nine months later. Emma Brown continued to publish the Chief until March of 1889 when a notice appeared in various papers saying that she had suspended publication on account of poor health. Emma died of breast cancer on June 4, 1889. An obituary in the Green Bay Press-Gazette said she had battled cancer for two years and only in her final weeks did her friends learn that anything serious was affecting her health. The paper praised her, saying:

She has lived a noble, self-sacrificing life, and the spectacle of this woman, enduring the ravages of a fatal disease and steadily pursuing her chosen work, involving hard physical labor at times to within a few weeks of the end, and for the betterment of others, is one to aspire noble thoughts and deeds.

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s diaries (August 3, 1874; September 7, 1874; October 2, 1875); Wisconsin Chief (August 23, 1873; September 1874); Emma Brown’s letter to Lavinia Goodell (July 11, 1879); Genevieve G. McBride, On Wisconsin Women (University of Wisconsin Press 1993); Eau Claire news (March 15, 1889); Wisconsin State Journal (June 5, 1889); Green Bay Press-Gazette (June 5, 1889); Maria Goodell Frost, Life of Lavinia Goodell (unpublished biography).