“Health is more important than writing.”

Clarissa Goodell to Lavinia Goodell, August 5, 1861

Lavinia Goodell grew up in a family that believed in healthy living practices. Good nutrition, scrupulous sanitary customs, and regular exercise were part of their daily program. Here is how Lavinia’s sister, Maria Frost, described the household routine at the time of Lavinia’s birth in 1839:

The habits of the household [included] regularly stated hours of rising and retiring, the table regimen was according to the principles of Dr. Sylvester Graham, with some exceptions suggested by constitutional needs, as learned by careful experience and strong common sense.

Sylvester Graham may not be a household name today, but a version of a product he developed is in many homes. Yes, Dr. Graham was the inventor of the graham cracker.

Dr. Graham was a Presbyterian minister who advocated for an ascetic lifestyle that shunned stimulants such as coffee and tea, alcoholic beverages, and animal products and encouraged fresh air, clean living, and exercise. In 1829, Graham invented the graham cracker, which was made with unsifted whole wheat flour. (Graham would not recognize his namesake crackers today, which are made with refined bleached flour, high fructose corn syrup, and artificial flavor.) Graham also invented high fiber graham bread and graham flour and abhorred commercially made breads, making him very unpopular with bread makers.

When a cholera epidemic epidemic swept through New York City in the summer of 1832, Dr. Graham gave a series of popular lectures on how the adoption of correct habits of living could prevent disease. (Click here to learn about the 1866 cholera epidemic, which struck when Lavinia was living in Brooklyn.) Graham also opened a number of temperance boarding houses.

William Goodell, Lavinia’s father, was living in lower Manhattan in 1832 and was editor of the Genius of Temperance. In order to avoid cholera, he sent his wife, Clarissa, and their young daughter Maria to Providence, Rhode Island to stay with Clarissa’s parents. William remained in the city and lodged in a Graham boarding house operated by Mrs. Asenath Nicholson. Fellow lodgers included Lewis and Arthur Tappan, successful businessmen and early leaders in the abolition movement, and a young Horace Greeley.

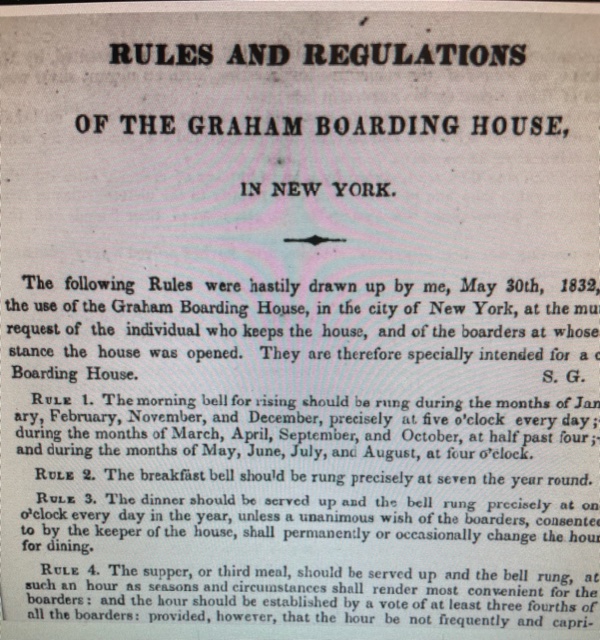

The rules in a Graham boarding house were strict, and living conditions were spartan. The morning bell for rising rang between 4:00 and 5:00 a.m. Before the breakfast bell rang at 7:00, boarders were encouraged to wash themselves thoroughly with cold water and rub themselves “very briskly & smartly with a very coarse towel or flesh brush, or both, till his skin feels in a comfortable glow.” After that, boarders were urged to engage in 30 to 60 minutes of active exercise. Boarders were not allowed to sleep on feather beds. Any boarder caught drinking tea, coffee, chocolate or narcotic liquors, or using tobacco would be requested to leave.

According to the memorial booklet published after his death, William Goodell adhered to the simple diet he adopted at this time for the remaining forty-five years of his life, although he and his family members never strictly abstained from eating meat. (Chicken pies were a Goodell family favorite.)

Clarissa Goodell wrote to her husband from Rhode Island in July of 1832 assuring him that she was taking good care of little Maria and that they, too, were following an austere diet. “I don’t let her eat everything. Her principal food is rice and molasses.” Clarissa told her husband that “if it is your wish I could not refuse” to return to New York “in case you should be sick,” although her friends advised against it. She said she was happy “that you keep quiet and don’t work as hard as you used to do” and encouraged William to change his sheets often and wear clean shirts and collars.

For the remainder of their lives, the Goodells continued to trust in Graham crackers and flour as healthful foods. In the summer of 1861, when Lavinia was staying with Maria near Buffalo, New York awaiting the birth of Maria’s daughter Harriet, Clarissa urged her younger daughter not to overdo and not to try to write any articles for William’s antislavery newspaper, the Principia. She wrote, “Health is of more importance than writing. I felt as though I wanted to have this journey benefit you. Your father has bought me some excellent graham crackers so I have given up having the bread baked for a few weeks.” And in 1868 when she was suffering from congestion of the lungs, Clarissa reported, “Have lived on toasted graham bread and sage tea for a week.”

As an interesting postscript, in spite of his holistic lifestyle, Dr. Graham died at age 57.

Sources consulted: Clarissa Goodell’s letters to Lavinia Goodell (August 5, 1861; February 15, 1868); Maria Frost, Life of Lavinia Goodell (unpublished manuscript available at Berea College Special Collections & Archives, Berea, Kentucky); Clarissa Goodell’s letter to William Goodell (July 12, 1832); “In Memoriam. William M. Goodell,” (Guilbert & Winchell, Printers, Chicago, 1879); Sylvester Graham, Â Lecture on Epidemic Diseases Generally and Particularly the Spasmodic Cholera (Published by Mahlon Day, New York, 1833).